Black Hills/Paha Sapa, United States

The Black Hills are considered a sacred place by the Lakota people and are representative of the entire four-state region of South Dakota, Wyoming, Montana and North Dakota, where thousands of uranium mines or exploration wells are located. For more than 40 years, the local population has been exposed to the radioactive legacy of the former uranium rush.

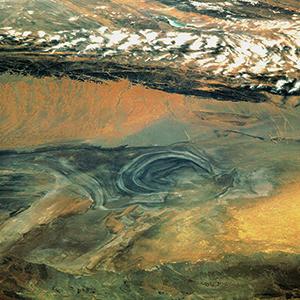

Photo: View over the Black Hills National Forest. According to the environmentalist organization “Defenders of the Black Hills,” there are more than 270 unsealed uranium mine shafts and thousands of contaminated exploration wells in this region alone. Many are filled with water and there is the constant danger of leaks and spills.

Photo credit: Navin75 / creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-sa/2.0

History

Because of their enormous amount of natural resources, the Black Hills have been extensively mined for centuries. The Native American Lakota nation shares a long history with the mountains, which they consider a sacred spiritual site and call “Paha Sapa.” In 1868, the U.S. government signed the Fort Laramie Treaty with the Great Sioux Nation, which guaranteed the Lakota that no white settlement would take place in the Black Hills. Only a few years later, however, gold was discovered in the area and, with the ensuing gold rush, the treaty was no longer honored.

Apart from gold mining, which still plays an important role in the region today, the discovery of uranium in the 1950s has had an immense impact on the life of the Lakota. Uranium ore was initially mined in the southwestern Black Hills near the city of Edgemont, but very soon more mines opened all over the Black Hills and the nearby Cave Hills. Between 1951 and 1964, the yield of the mines in the region exceeded 680,000 kg of yellowcake, the refined uranium dust needed for nuclear warheads and reactors. In the 1980s, environmentalist groups managed to stop uranium mining in the area. Because of regulations and limited efforts to rehabilitate the region, however, the abandoned mines were never properly sealed or protected from leaks and spills.

Health and environmental effects

The old mine shafts, which were not adequately sealed, are a major concern of the people living in the region. According to the environmentalist organization “Defenders of the Black Hills,” there are hundreds of these unsealed mines, as well as thousands of exploration wells and drill holes, some more than 200 m deep, scattered all across the four-state area. Many are filled with water and there is the constant danger of leaks and spills into the surrounding creeks that can potentially contaminate underground aquifers or the larger Cheyenne and Missouri rivers. Field studies in the years 1999–2000 found radiation doses of 40 mSv/h, or about 200–400 times natural background radiation.

After the U.S. Geological Survey found elevated concentrations of dissolved uranium in the Arikaree aquifer below the Lakota reservation of Pine Ridge, the local council asked the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) to investigate water and air samples. They found increased concentrations of alpha emitters in drinking water supplies as well as unhealthy levels of radon gas in private residences at Pine Ridge. The “Defenders of the Black Hills” also conducted their own investigations in cooperation with Energy Laboratories and detected alpha emitters exceeding recommended dose levels. Drinking this water and ingesting the radioactive particles can cause cancer and other diseases.

Within the reservation, an extremely high number of people suffer from cancer, diabetes and kidney failure. High incidences of stillbirths, miscarriages and deformities are also reported among the population of the Black Hills. Beyond the small preliminary air- and water-studies however, no investigations of the evident health problems of Pine Ridge residents have been undertaken so far.

Outlook

Although uranium mining was stopped in the 1980s, new mines were commissioned in the 1990s. In 2011, the Canadian company Powertech announced plans to restart uranium mining in the Black Hills near Edgemont. Environmentalists are concerned about further contamination of the underground aquifers of the Black Hills region, four of which would be affected by the planned mine.

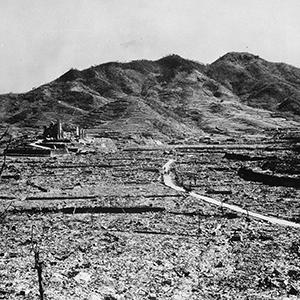

In addition to the social and economic problems of reservation life, the Lakota suffer from the legacy of four decades of uranium mining. To this day, there has not been an adequate scientific workup of the Lakota’s health problems. Therefore, the effects of further radioactive contamination of the region through continued uranium mining cannot even be predicted. What can be said with certainty, however, is that the health of the local population has been sacrificed for the profits of the nuclear industry. Like so many people around the world, who are suffering from the industry’s endless appetite for cheap uranium for its warheads and power plants, the Lakota, too, can rightly be called Hibakusha.

References

- White Face C. “Fact Sheet on Uranium Mining and Nuclear Pollution in the Upper Midwest.” Defenders of the Black Hills, www.mining-law-reform.info/Attach3.htm

- Stone J et al. “Final Report: North Cave Hills Abandoned Uranium Mines Impact Investigation.” U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, April 18, 2007, p.10-11. http://uranium.sdsmt.edu/Downloads/NCHUraniumMinesImpactReport04-18-17.pdf

- Heakin AJ. “Water Quality of Selected Springs and Public-Supply Wells, Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, South Dakota, 1992-97.” Water Resources Investigation Report 9-4063, U.S. Geological Survey, 2000. http://pubs.usgs.gov/wri/wri994063/wri994063.pdf

- “Pine Ridge Indian Reservation (aka Cheyenne River Basin).” Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Health Consultation, March 31, 2010. www.atsdr.cdc.gov/hac/pha/pha.asp?docid=1069&pg=1#appb

- White Face C. “Report on Water Tests for Radioactive Contamination.” Defenders of the Black Hills, March 2011. http://www.defendblackhills.org/document/waterreport32011.pdf

- White Plume D. “Crying Earth Rise Up! Environmental Justice & the survival of a people: Uranium mining & the Oglala Lakota people.” Owe Aku – Bring Back the Way, Educational Campaign Winter 2008-2009. www.mining-law-reform.info/LakotaSurvival.pdf