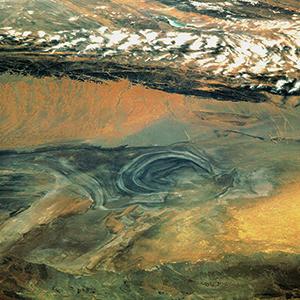

In Ekker, Algeria

At its Algerian nuclear test site, In Ekker, France performed 13 underground nuclear detonations, causing vast radioactive contamination of soil, air and possibly even underground aquifers, and directly exposing hundreds of people to radiation. To this day, the casualties have not been properly compensated and the extent of radioactive contamination has not been assessed.

Photo: 2010. Victims of radiation exposure standing outside the former test site of In Ekker, about 170 km away from the town of Tamanrasset. Radioactive material continues to seep out of the mountain, where France conducted its nuclear tests, and contaminates local soil and ground water. © Zohra Bensemra/Reuters/Corbis

History

In Ekker is located on the principal route through the Sahara desert in the southern part of Algeria in a region populated by nomadic tribes and passing caravans. After a series of atmospheric nuclear tests in Reggane caused concern among Algerian politicians, France began testing below ground at In Ekker in November 1961. Algeria was a French colony until 1962. Even after the Évian Accords ushered in Algerian independence, testing continued, as a special clause permitted nuclear tests in Algeria for five more years. Thus, until February 1966, 13 more nuclear bombs were detonated in tunnels in the Hoggar mountain range.

Between May 1964 and March 1966, the French army also carried out five plutonium dispersal experiments, codenamed “Pluto.” These tests aimed to simulate a plutonium bomb accident and to determine how far the desert winds could carry and disperse radioactive fallout.

Health and environmental effects

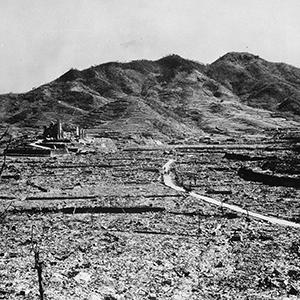

Because of rock fissures or faulty sealing, at least four of the 13 nuclear detonations led to massive releases of radioactive gases into the atmosphere. The most infamous of these tests, code-named “Béryl,” took place in May 1962. After the explosion, containment measures failed, and a radioactive cloud spread 2.6 km into the atmosphere, while contaminated molten rocks were hurled from the tunnel. A general panic followed and the 2,000 spectators, including two French ministers, fled. Increased levels of radioactivity were detected up to several hundred kilometers away. About 100 French citizens and an unknown number of Algerians in the immediate vicinity were exposed to high levels of radiation (50-600 mSv). These doses correspond to about 2,500 to 30,000 chest x-rays and are much higher than normal background radiation of 0.0003 mSv/h. As a result, many of the victims suffered from cancer or other diseases, including the French Minister of State, Gaston Palewski, who was present during the test and subsequently died of leukemia in 1984.

In the local population, there are reports of cancers, cataracts and infertility attributable to radioactive exposure, but due to a lack of proper medical care and scientific interest, no epidemiological studies have been performed to date.

Through the nuclear detonations, large areas of the desert were turned into radioactive wastelands. Through washout of contaminated soil, underground aquifers and nearby oases may also have been irradiated. Contaminated debris, scrap metal and technical instruments from the test site remain in and near the tunnels. Much of this debris has been removed by thieves and nomads, spreading radioactivity all over the region.

Outlook

The Béryl explosion left a lasting stream of radioactive lava outside of the tunnel entrance. In 2007, independent researchers measured radiation levels at this lava stream of 0.1 mSv/h (about 350 times normal background radiation). Without maps exist to indicate radioactively contaminated areas, nomadic communities and their herds entered the contaminated regions, unaware of the potential danger. In 1999, the Algerian government finally erected a 40 km-long fence to prevent access to the contaminated mountain. Still, the danger is not contained and further medical and environmental research is urgently needed.

Time and time again, Algerian NGOs and French veteran unions have demanded compensation from the French government, which has always claimed that no injury to military or civilian personnel resulted from their nuclear tests. In 2009, French lawmakers finally drafted a bill which would offer compensation payments to people present at nuclear tests who contracted one of 18 types of cancer designated by the UN as radiation-induced.3 Forty years after the initial tests, however, this symbolic gesture comes too late for many of the Hibakusha of In Ekker, whose health was compromised by the use of nuclear weapons.

References

- Barrillot B. “French Nuclear Tests in the Sahara: Open the Files.” Science for Democratic Action, Institute for Energy and Environmental Research, April 2008. http://ieer.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/15-3.pdf

- “Radiological Conditions at the Former French Nuclear Test Sites in Algeria.” International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Vienna, 2005. www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/publications/PDF/Pub1215_web_new.pdf

- “France to pay nuclear test compensation.” BBC News Website, June 9, 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/8076685.stm