Shiprock/Tsé Bit’ A’í, United States

The uranium mine at Shiprock left a legacy of health and environmental damage that affects indigenous Navajo communities to this day. Moreover, pressure is mounting to reopen the mines in order to fuel new generations of nuclear warheads and power plants.

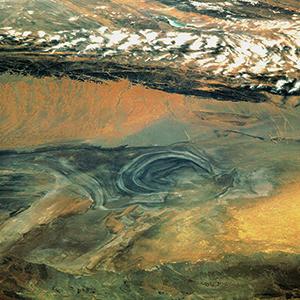

Photo: The vicinity of a former uranium mine. When mines were decommissioned in the 1970s, more than 200 tunnel openings were left unsealed and enormous piles of radioactive waste rock and tailings were abandoned without adequate protective measures. © Manuel Quinones

History

Named for a prominent rock formation, Shiprock is a town in northwest New Mexico and part of the Navajo Nation, the largest indigenous reservation in the United States. For almost three decades, uranium was mined here in order to produce fissile material for U.S. nuclear weapons and power plants. Mining around Shiprock began in the 1940s, and was especially active in the following two decades, when U.S. nuclear weapons production peaked. The Vanadium Corporation of America and Kerr-McGee were the principal mining companies. Few, if any, health and safety regulations existed to protect the poorly paid miners and mill workers, most of whom were recruited from local Navajo communities. While the connection between uranium mining and lung cancer had been established as early as the 1930s, and the dangers of radon gas, which permeates uranium mines, were well known, this information was withheld from the miners and their families. In fact, there is no word for “radiation” in the Navajo language. When mining operations ceased in the 1970s, more than 200 tunnel openings were left unsealed and enormous piles of radioactive waste rock and tailings were abandoned without adequate protective measures.

Health and environmental effects

During the 1960s, studies found dramatic spikes in lung cancer and other illnesses in the region. Of the 150 Navajo who worked at the uranium mines in Shiprock, 133 had died of lung cancer or various forms of fibrosis by 1980. Lung cancer risk in Navajo uranium miners is 20–30 times greater than for other Navajo men. Moreover, 67 % of lung cancer cases in Navajo men between 1969 and 1993 have been attributed solely to uranium mining, without any relevant confounding factors. A frequently cited article described a statistically significant association between uranium mining and congenital birth defects among Navajos born in Shiprock.

As a reaction to these worrying developments, the miners organized a union and formed the Uranium Radiation Victims Committee, which educated people about the hazards of uranium mining. The group sued the state and federal governments for compensation and sought stricter legislation to protect people and the environment from the effects of uranium mining. In 1990, the U.S. Congress passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act. That same year, the Navajo Tribal Council formed the Office of Navajo Uranium Workers to create a worker registry and provide medical care to those affected by radiation. In 2010, as part of a $270 million settlement with Kerr-McGee, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Navajo nation received $14.5 million to address uranium contamination, including $1.2 million specifically for Shiprock. To this day, however, up to 9.5 million liters of contaminated water leaks into the San Juan River from Shiprock uranium mills every year. The EPA stated that “approximately 30 % of the Navajo population does not have access to a public drinking water system and may be using unregulated water sources with uranium contamination.”

Outlook

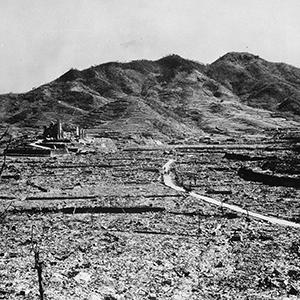

Today, Shiprock is usually associated with the 400,000 m² nuclear waste dump, containing the waste rock and tailings from more than 22 uranium mines and mills. In the mid 2000s, studies showed that more than 1.8 million liters of groundwater were contaminated with uranium, selenium, radium, cadmium, sulfate and nitrate. Parts of the San Juan River showed uranium concentrations that were between 47 to 97 times above official safety levels. While tribal officials have noted progress on groundwater clean-up in Shiprock, they have criticized the ongoing failure of the U.S. government to assess the health impacts of decades of radioactive exposure of miners and local populations. In their search for cheap uranium for its civil and military nuclear programs, the U.S. government knowingly exposed the local population to radioactivity, turning the Navajo of Shiprock into Hibakusha.

References

- Brugge et al. “The Navajo people and uranium mining.” UNM Press, 2006.

- Ali SH. “Mining, the environment, and indigenous development conflicts.” University of Arizona Press, 2003.

- Gilliland et al. “Uranium Mining and Lung Cancer Among Navajo Men in New Mexico and Arizona.” J Occup Environ Med 42(3):278-283, March 2000. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10738707

- Shields et al. “Navajo birth outcomes in the Shiprock uranium mining area.” Health Physics 1992;63:542-551. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1399640

- “Addressing Uranium Contamination in the Navajo Nation.” Website of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency EPA. www.epa.gov/region9/superfund/navajo-nation

- Robinson P. “Uranium mill tailings remediation performed by the U.S. DOE.” Southwest Research and Information Center, Albuquerque, 2004. http://www.sric.org/uranium/docs/U_Mill_Tailing_Remediation_05182004.pdf