Reggane, Algeria

The French army conducted four atmospheric nuclear tests near Reggane, Algeria in 1960 and 1961, contaminating the Sahara desert with plutonium, exposing soldiers, workers and local Tuareg to radioactive fallout, and causing long-term health effects like cancer, infertility and genetic mutations.

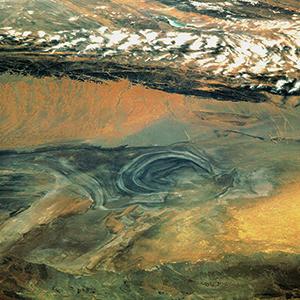

Photo: The outskirts of Reggane. Even 45 years after the end of nuclear testing, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) still found increased levels of radioactivity in the entire test area of Reggane and warned of the inhalation of airborne pieces of radioactively contaminated sand.

History

In 1945, France established the French Atomic Energy Commission (CEA), which was given authority over all nuclear affairs – scientific, commercial and military. In the 1950s, France began mining uranium and processing it into weapons-grade plutonium. The construction of nuclear weapons was completed in a few years and the first tests were organized in French-occupied Algeria, 50 km southwest of the Saharan city of Reggane. The first French nuclear test, code-named “Gerboise Bleue” (“Blue Desert Rat”), was detonated on February 13, 1960 with an explosive yield equivalent to 70 kilotons of TNT. The following year, three more atmospheric tests (“Gerboise Rouge,” “Gerboise Verte” and “Gerboise Blanche”) were conducted in Reggane, before protests forced the French government to switch to underground testing at In Ekker in the Algerian mountains.

The French newspaper “Le Parisien” uncovered that in April 1961, 300 French soldiers were deliberately ordered into the contaminated nuclear test area of Gerboise Verte in order to study the “physiological and psychological effects produced on man by nuclear weapons, so as to obtain necessary information to physically and mentally prepare modern warriors.” Five years after its independence from France in 1962, Algeria received full sovereignty over the heavily contaminated Reggane test site.

Health and environmental effects

Ten thousand soldiers, workers for the nuclear program and the local Tuareg population were directly exposed to radioactivity from the nuclear tests. Countless others were exposed to nuclear fallout, which spread across Northern Africa. Increased levels of radioactivity were detected as far away as the Sudanese capital of Khartoum, 3,200 km from Reggane. A French Senate report stated that French soldiers present at the tests were exposed to doses between 42 and 100 mSv – about 20–50 times the annual background radiation (about 2.4 mSv per year) or the equivalent of approximately 2,000–5,000 chest x-rays (0.02 mSv per radiograph). These figures do not include the levels of internal radiation caused by inhalation of radioactive plutonium or other radioisotopes in dust or sand, which play an important role in the development of cancer, especially for the people who live far from the actual explosion.

Forty five years after the end of nuclear testing, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) still found increased levels of radioactivity in the entire test area of Reggane and warned of the inhalation of airborne pieces of radioactively contaminated sand. The sites are not properly fenced off or guarded, and large amounts of radioactively contaminated scrap metal have been stolen and sold on the black market.

To this day, no proper epidemiological studies on the health effects of the nuclear tests at Reggane on workers, soldiers and local Tuareg have ever been conducted, despite reports of increased cancer rates and congenital malformations in the region. In 2008, the French Nuclear Testing Veterans’ association, “Aven,” conducted a survey of more than 1,000 veterans and found that 35 % had one or more types of cancer and one in five had been diagnosed with infertility. According to Aven, the group of Reggane veterans suffer from a range of illnesses, including leukemia and cardiovascular problems and even their children and grandchildren showed an unusually high incidence of severe health complications, which could be associated with genetic damage.

Outlook

In March 2009, the French government finally offered to compensate casualties of nuclear testing, but casualties say the eligibility requirements for compensation are too restrictive and the entire compensation scheme too difficult to access. This applies especially to the local Tuareg population – the Hibakusha of French nuclear testing in Reggane. Comprehensive and independent epidemiological studies are needed in order to assess the extent to which nuclear testing affected the health of those who participated in the tests and those how are living around Reggane and other nuclear weapons test sites. The file on Reggane is still not closed.

Further information

The French documentary “Vent de sable“ shows Interviews with experts and affected Tuareg: www.youtube.com/watch?v=HKm6MXasgVo

References

- “13 February 1960 – The First French Nuclear Test.” Website of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO). www.ctbto.org/specials/testing-times/13-february-1960-the-first-french-nuclear-test

- “Quand les appelés du contingent servaient de cobayes.” Le Parisien, February 16, 2010. www.leparisien.fr/faits-divers/quand-les-appeles-du-contingent-servaient-de-cobayes-16-02-2010-817293.php

- “Les essais nucléaires Français.” Website of the French Senate. www.senat.fr/rap/r01-207/r01-2073.html

- “Radiological Conditions at the Former French Nuclear Test Sites in Algeria.” International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Vienna, 2005. www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/publications/PDF/Pub1215_web_new.pdf

- Valatx JL. “Conséquences sur la santé des essais nucléaires français – Résultats sur 1800 questionnaires.” Website of the Association des vétérans des essais nucléaires (AVEN). www.aven.org/aven-acceuil-actions-medicales-enquete-sante