Tōkai-mura, Japan

The accident at the Tokai-mura nuclear facility in 1999 irradiated a total of 667 people, two of whom died from acute radiation poisoning. Tokai-mura was Japan’s worst nuclear crisis before the Fukushima meltdowns and serves as an example of the dangers inherent in every link of the nuclear chain.

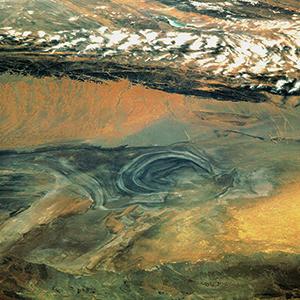

Photo: Aerial view of the Tokai-mura compound in 1974. The Japanese Atomic Energy Research Institute was established here in 1956, followed by nuclear fuel factories, reprocessing plants and Japan’s first nuclear power plant in the 1960s. Today, Tokai-mura is dotted with 15 nuclear sites. © National Land Image Information (Color Aerial Photographs), Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism

History

Tokai-mura, a small town 120 km northeast of Tokyo, is often referred to as the heart of Japan’s nuclear industry. The Japanese Atomic Energy Research Institute was established here in 1956, followed by nuclear fuel factories, reprocessing plants and Japan’s first nuclear power plant in the 1960s. Today, Tokai-mura is dotted with 15 nuclear facilities, including a fuel conversion plant operated by the Japan Nuclear Fuel Conversion Company (JCO). On September 30, 1999, the plant was producing mixed oxide nuclear fuel for the experimental Joyo fast reactor. Normally, uranium yellowcake is dissolved in nitric acid. In order to speed up the process and save money, three of the plant’s workers filled the precipitation tank with 16.6 kg of uranium instead of the permitted 2.4 kg, creating a critical mass and setting off a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction, which released massive amounts of neutron- and gamma-radiation over a period of 20 hours. 161 people were evacuated and approximately 310,000 residents within 10 km of the plant were asked to stay indoors as radioactive particles like iodine-131 were released into the atmosphere through the ventilation system.

Health and environmental effects

The three workers involved in the accident were exposed to 16–20, 6–10, and 1–4.5 Sv, respectively. Despite immediate intensive care treatment, the first two workers died in the following months, while the third worker eventually recovered. The story of one of them, Hisachi Ouchi, is told in the book “A slow death – 83 days of radiation sickness.” Despite the most modern medical treatment available, he ultimately died from internal bleeding, immunodeficiency and multiple organ failure. According to the official report by Japan’s Science and Technology Agency, 169 other employees were irradiated with up to 48 mSv. This corresponds to about 2,400 chest x-rays (0.02 mSv per examination). 235 local residents were exposed to as much as 16 mSv, while 260 rescue workers and journalists received up to 9.2 mSv. The International Commission on Radiation Protection recommends an additional 1 mSv as a dose limit for the general public, over and above the natural background radiation in Japan, which is about 1.5 mSv per year.

In a 2001 study by the Citizens’ Nuclear Information Center, 1,182 households were surveyed in the Tokai-mura area. 35 % of residents complained of new physical or mental symptoms such as headache, weakness, sleep disorders or anxiety following the accident. The correlation between the distance to the plant and symptoms proved to be significant. Tokai-mura may have been Japan’s worst nuclear disaster before Fukushima, but it was by no means an exception. Events such as this occur in Japan’s under-regulated nuclear industry with an alarming frequency: numerous radioactive leaks occurred in the Tsuruga nuclear plant in the 1980s, irradiating more than 200 people; also, there have been several incidents of fire and accidents at nuclear facilities in Tokai-mura, such as the explosion on March 11, 1997, which exposed 37 people to high levels of radiation.

Outlook

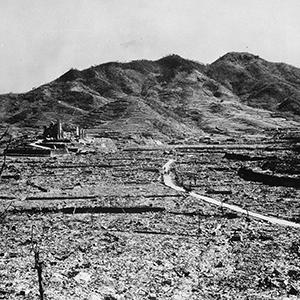

The investigations of the accident revealed that JCO allowed unsafe procedures in order to save time and money. In addition, the workers had no proper qualifications and had not received proper training. Moreover, no emergency routines had been prepared, as criticality events were considered unrealistic. The poor crisis management and restrictive information policy during and after the accident were criticized by scientists, politicians and reporters, but little changed in terms of a nuclear safety culture, as the meltdowns of the Fukushima reactor in 2011 painfully demonstrated. In Tokai-mura, meanwhile, people have begun to doubt the safety of old reactors. While Tokai-1, Japan’s oldest nuclear reactor, was decommissioned recently, the Tokai-2 reactor is still running. Following the Fukushima disaster, Tokai-mura’s mayor, Tatsuya Murakami, has now called on the Japanese government to decommission it, citing safety issues. He does not want to see more of his citizens become casualties of the nuclear industry – become Hibakusha.

References

- “Report on the preliminary fact finding mission following the accident at the nuclear fuel processing facility in Tokaimura, Japan.” International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), 1999. www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/Publications/PDF/TOAC_web.pdf

- NHK-TV Tokaimura Criticality Accident Crew. “A Slow Death: 83 Days of Radiation Sickness.” Vertical, 2008

- “Radiation in environment.” Website of the Japanese Ministry for Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). www.kankyo-hoshano.go.jp/04/04-1.html

- Hasegawa et al. “JCO Criticality Accident and Local Residents: Damages, Symptoms and changing Attitudes.” Citizens Nuclear Information Center (CNIC), June, 2001. www.cnic.jp/english/publications/pdffi les/jco_residents_font.pdf

- “Accidents 1980s”; “Accidents 1990s.” Nuclear Files.org, Website of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation. http://nuclearfiles.org/menu/key-issues/nuclear-weapons/issues/accidents/index.htm

- “Tokaimura nuclear accident from an occupational safety and health viewpoint.” Japan Occupational Safety and Health Resource Centre, Newsletter No. 21, August 2000. www.amrc.org.hk/alu_article/occupational_health_and_safety/tokaimura_nuclear_accident_from_an_occupational_safety_an