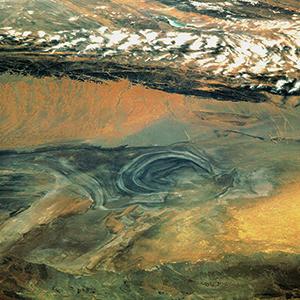

Mayak/Kyschtym, Russia

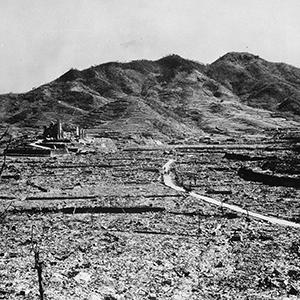

Through a series of accidents and spills, the Russian nuclear facility at Mayak contaminated more than 15,000 km² with highly radioactive waste. In 1957, the so-called Kyshtym accident alone made large parts of the Eastern Urals uninhabitable. Thousands of people had to be relocated and, to this day, the region affected by nuclear fallout is considered one of the most contaminated places on earth.

Photo: Cows grazing beside the contaminated Techa River. Until 2006, no signs warned of radioactivity here. Between 1949 and 1956, 100 Peta-Becquerel of radioactive waste was dumped in the Techa river system – including strontium-90, cesium-137, plutonium, and uranium. Photo: © Ecodefense/Heinrich Boell Stiftung Russia/Slapovskaya/Nikulina

History

The Mayak Production Association (MPA) was the first and largest nuclear facility in the Soviet Union, covering an area of about 200 km² between the cities of Ekaterinburg and Chelyabinsk. Initially built to provide plutonium for Soviet nuclear weapons, five nuclear reactors were constructed in the city called Chelyabinsk-40 (now renamed Ozyorsk) between 1945 and 1948. The facility was continually expanded until the production of weapons-grade plutonium was stopped in 1987 and the facility was gradually downsized. Between 1949 and 1956, 100 Peta-Becquerel (Peta = quadrillion) of radioactive discharge, containing strontium-90, cesium-137, plutonium, and uranium was released into the Techa river system. By comparison, radioactive emissions from the Fukushima nuclear disaster into the Pacific Ocean have been estimated at 78 PBq. At least eight large-scale accidents took place at Mayak. In 1967, for example, dispersion of radioactive dust from the Karachay radioactive waste dump contaminated 1,800 km² with cesium-137. The most notorious accident, however, took place on September 29, 1957. The explosion of a radioactive waste tank containing 740 PBq of fissile materials radioactively contaminated an area of more than 15,000 km². After Chernobyl and Fukushima, this catastrophe, often named after the adjacent town of Kyshtym, ranks as the third largest nuclear disaster in history (level 6 on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale “INES”). A lasting legacy of the catastrophe is the 300 km long and 30–50 wide Eastern Ural Radioactive Trace, which was heavily contaminated by nuclear fallout. In some parts, concentrations of radioactive strontium-90, a known cause of leukemia, exceed 7.4 Mega-Becquerel per m² (Mega = million). By comparison, after Chernobyl, all areas with radioactive contamination of more than 0.5 MBq/m² were permanently evacuated.

Health and environmental effects

Nearly 19,000 workers were employed by the MPA until 1973. These people received the highest doses of radiation due to numerous accidents and spills. For the 10,000 workers hired before 1959, the mean cumulative external dose was about 1,200 mSv. This dose corresponds to about 60,000 chest x-rays. From this external dose alone, about 24 % of the workers would be expected to develop cancer. But the number of cancer cases in the Mayak workers cohort is probably much higher, as internal irradiation has an even larger impact on cancer risk. More than 1,000 workers incorporated between 1,500 and 172,000 Bq of plutonium each. With a dose-factor of 0.00014 Sv/Bq, this amounts to an internal radiation dose of about 0,2–24 Sv. A dose of 10 Sv is considered fatal; at a dose of 5 Sv, every second person is estimated to die from acute radiation effects. Acute radiation sickness usually affects all people who receive doses of more than 1 Sv. At doses below 1 Sv, the long-term consequences of radiation outweigh the acute radiation effects. The WHO assumes that at dose rates of 0.1 Sv, the leukemia risk is about 19 %, rising by another 19 % for every additional 0.1 Sv of radiation exposure. The Mayak workers’ relative risk of developing bone cancer was found to be eight times higher than that of the general population; the risk for developing liver cancer was 17 times higher.

In addition to the workers, the nearly 300,000 residents of the contaminated regions affected. The estimated collective lifetime dose to this population is about 4,500 Person-Sv, about 60 % of the collective lifetime dose calculated after the Chernobyl meltdown. People living near Mayak or the Techa river were exposed to an average lifetime dose of up to 1,700 mSv from a combination of external radiation and the ingestion of radioactively contaminated drinking water and food. At such high dose levels, approximately 34 % of the population are likely to develop cancer cases, which they would not have developed without radioactive contamination.

Chronic radiation effects and excess cases of leukemia, as well as tumors of lung, bone and liver have been found in the affected population, as well as a two- to five-fold increase in the frequencies of bone-marrow depression, chromosomal aberrations, miscarriages and still-births. Due to military censorship, people were not informed about the threats of radioactivity, while the true extent of radioactive contamination and its public health impact were never adequately documented or investigated.

Outlook

Today, about 14,000 workers are still working at Mayak, mainly producing plutonium, uranium and other radioactive substances for the nuclear energy industry. Mayak also hosts Russia’s only nuclear reprocessing and waste treatment facility. Most decommissioned Russian nuclear warheads eventually end up in Mayak. Although nuclear contamination in the surrounding areas has decreased by about a factor of three in the past decades, the region around Mayak is still considered one of the most radioactively polluted place on earth. Reservoir lakes in the Techa River are still used as radioactive waste dumps, further polluting the river system and exposing people to continued radioactivity. The Hibakusha of Mayak have suffered so much under Russia’s nuclear ambitions, which have paid little regard to the health and lives of the local population. Now, large-scale epidemiological studies and decontamination projects are urgently required in order to protect these people from further harm.

References

- Standring WJF. „Review of the current status and operations at Mayak Production Association“. Strålevern Rapport 2006:19, Norwegian Radiation Protection Authority (NRPA), 2006. www.nrpa.no/dav/1fbb52ea04.pdf

- „BEIR VII report, phase 2: Health risks from exposure to low levels of ionizing radiation“. National Academy of Sciences Advisory Committee on the Biological Effects of Ionizing Radiation, 2006. www.nap.edu/openbook.php? record_id=11340&page=8

- Koshurnikova et al. „Studies on the Mayak nuclear workers: health effects“. Radiation and Environmental Biophysics, 41:1, 29-31, 2002. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12014404

- WHO. „Health risk assessment from the nuclear accident after the 2011 Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami, based on a preliminary dose estimation“, 28.02.2013, p 32. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/78218/1/9789241505130_eng.pdf

- Standring et al. „Mayak Health Report“. Strålevern Rapport 2008:3, Norwegian Radiation Protection Authority (NRPA), 2008. www.nrpa.no/dav/19bdfc616e.pdf

- „Atom ohne Geheimnis“, IPPNW, Moskau-Berlin, 1992